[This article originally appears in issue #14 of White Fungus magazine, reprinted with publisher’s permission. Subscribe to White Fungus here]

For five decades, the Stasi managed to painstakingly craft what was at the time the world’s most sophisticated surveillance state. The secret police of the German Democratic Republic’s Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (shorthand: Stasi) induced an era of fear among the East German population.

Not because they were killers, although some definitely were, but because of their manipulation capabilities. They could remove any chance for your future employment, ban your child from entering college, ruin one’s art career and even drive one to suicide. What made the Stasi particularly unique was that they had their surveillance and tracking methods down to a science. The Stasi were able to monitor and judge a situation from a far covertly and then ‘guide’ it towards an outcome they desired.

Most of the Stasi’s ‘successful’ operations were on specific targets, rarely ever were ‘legitimate threats’ detected or thwarted through massive sweeps. One senior Stasi official said their main weakness was that they could “listen in on everything”. In practice, spying on everyone simultaneously had a fundamental flaw – excesses of records made it tedious and time consuming to find the needle in the haystack. Almost all East Germans felt the presence of the Stasi in some way, but a surprising amount of former GDR citizens explain that they ‘never did anything wrong’ and therefore presumably never attracted Stasi attention. It’s this disparaging view that gives us insight into what soft totalitarianism in the form of mass surveillance does to the psychology of a society.

What happens to a collective group who are conscious of their privacy being removed? An obvious answer is that people behave differently, adapt or change their behavior in accordance to being watched, even erasing a free thought that threatens the state before it’s even fully formed. When rumors ran rampant in the GDR of Stasi cameras in private bedrooms and bathrooms and the exploitation of one’s private sexual practices or orientation had become regular fodder for blackmail, Stasi presence was probably even felt in the bedroom. The GDR hid damning suicide statistics to present a preferable image to the outside world, and finding any surviving psychological surveys of the population as a whole is virtually impossible. Only by piecing together personal stories, media and documented history of daily life under the Stasi does it become clear the unsettling side effects blanket surveillance can create in the lives of an entire population.

Instead of outright killing (for attempting to cross into West Berlin) or harshly imprisoning (for dissent), the Stasi’s preferred methods reveal an institutional and operational belief that their target’s actions could be vulnerable to influence or even prediction via total observation and control. For a man whose son was killed by GDR guards for trying to steal scrap metal off a base, it meant being monitored for over a year to make sure he didn’t raise too much of a stink about the murder. The expensive operation’s justification: his sister-in-law had spoken to a West German media outlet about the killings, which had subsequently cascaded into a worldwide story. Fearing further negative media attention, the Stasi staked out his apartment from across the road, made themselves a copy of his key, tapped his phone, and then settled in to await anything that piqued their interest. After a year of this sphere of surveillance which had now expanded to include his relatives, save for a few angry remarks about the murders, it was clear his interest had waned. The Stasi were finally satisfied that he wasn’t angling to attract media attention or escalate his cause. This is just one example of the ridiculous amount of resources dedicated to predicting the behavior of a single person suspected of merely being capable of causing embarrassment for the GDR.  [Stasi Museum : Germany. Reprinted with permission from White Fungus]

[Stasi Museum : Germany. Reprinted with permission from White Fungus]

Typically if someone was found to have anti-GDR sentiments, the Stasi would try to recruit a co-worker or loved one (possibly themselves already a part-time informant). In the absence of a loyal informant, the Stasi would resort to exploiting fracture points between family members. In some instances, Stasi agents would emotionally manipulate people wanting to flee to the West by convincing their parents to beg them to stay. If a dissenter continued unabated under Stasi prying eyes, then things in his or her personal life could and often did start to go awry such as losing employment, and in rarer instances mysterious failing health.

In the time of the GDR, if you were concerned about the penetrating effect of the Stasi into everyday life, suspicious of your communication being monitored, or concerned that your wife was an agent, you wouldn’t be crazy, you’d be savvy. But, the very nature of a society like this makes bringing up these concerns in public or even among friends and colleagues an untenable risk. A citizen with a tendency to go after young women behind his wife’s back would be ripe pickings the Stasi, and blackmail was often used to coerce such people into becoming a spy for the state. In one specific case, a suspected pedophile was allowed to remain free as long as he became a full-time informant for the Stasi. Generally speaking, the worse your secrets were, the more the Stasi could milk you for all you were worth.

Exploiting hidden sexual appetites was just one tactic used to swell the ranks of non-voluntary informants. The Stasi collected many genres of compromising material beyond the sexual. Blackmail was a surefire way to inevitably push any individual into indentured servitude. Records show that 1 in 60 citizens were officially on the Stasi payroll, but unofficial reports estimate that as many as 1 in 6 citizens either were passing information to the Stasi or informing in some capacity on the people in their lives.

[This machine belonged to the postal inspection department of the Stasi. It automatically re-sealed envelopes. Reprinted with permission from White Fungus]

On January 15th, 1990, during the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Stasi Headquarters was overtaken and shut down by activists. It reopened shortly thereafter as Forschungs- und Gedenkstätte Normannenstraße, a Stasi museum open to the public. Visitors could now walk through the same spaces in which protesters had angrily breached the “‘shield and sword of the party’s” threshold and found Stasi officials still attempting to destroy incriminating files, even as they had run out of working shredders. The museum plays up the gadget aspect of Stasi spycraft reminiscent of crap films like James Bond. Necktie and pen cameras or wrist watch microphones may seem generic or crude by today’s standards, but it’s the oddities — cameras mounted in bird houses or car headlights, or hidden cameras inside tape recorders, and microphones inside watering cans and other garden accessories that leave the strongest impression. Keeping in mind that the GDR was economically isolated from the West, the miniature camera and microphone technology is in and of itself impressive.

The Stasi did indeed think outside the box, so considering the very unorthodox spy gadget concealment locations and how often and well hidden in public view they were, it’s not surprising the paranoia they instilled. The GDR in the 1980s was even able to reverse engineer an early IBM computer by procuring smuggled and cloned parts. Of course the main motivation was not to integrate programming or computer education into the GDR, it was to have cutting edge technology to database and catalog as much of the population as they possibly could. One of the strangest types of data they hoarded on the populace was olfactory, presumably to be used for police dogs. Scents were collected from clothing and personal effects and stored in labeled sealed jars. A storage room filled with these glass jars must have resembled a psychosexual experimental art installation.

[Stasi Museum: Germany. Reprinted with permission from White Fungus]

Even more outrageous methods of tracking targets included a special kind of radioactive dust sprinkled into vehicles or clothing to give agents the ability to ‘spy’ with radiation detectors on top of microphones and cameras. Much more sinister, however, is the rumored Stasi method of assassination via highly targeted radiation poisoning. One involved a prolonged exposure emanating from an innocuous-looking black box sitting on a table. It’s long been widely speculated that well known East German writers Jurgen Fuchs and Rudolf Bahro were assassinated by the Stasi in this way – given a carefully calibrated dose of radiation so that their deaths seemed natural and not immediate. The concept of a portable cancer box is not only bizarre, but justifiably terrifying. Even if this technique were rare, the whispers about such a punishment would undoubtedly inspire intense fear and panic in those that heard about it.

I stumbled upon this comment by a former citizen of the GDR, one Sabine Bohm on, of all places, Youtube (ironically in some ways Google, the company who owns Youtube makes the Stasi’s surveillance technologically seem quaint):

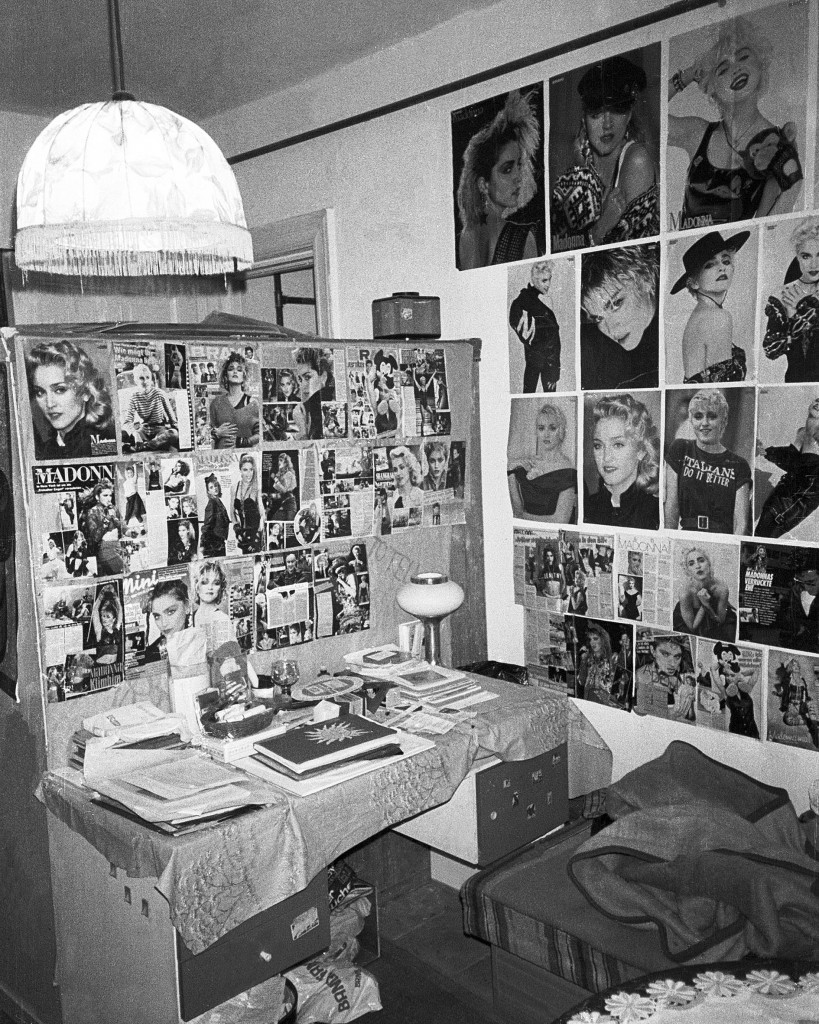

“I am glad I got out of this disaster in 1985. We were young creative, artistic people that was not wanted in the former GDR. Even without having done anything i had to sit 24 hours [in] jail and my diaries had been studied by the Stasi, who had broken into my flat and kept them with them. I was of course not so stupid to write my inner thought into it. The time was not easy” [Surveillance photo of a bedroom of a teen with alleged pro-Western sympathies. Reprinted with permission from White Fungus]

[Surveillance photo of a bedroom of a teen with alleged pro-Western sympathies. Reprinted with permission from White Fungus]

Sabine was aware the Stasi regularly read diaries. Although she kept one, Sabine simply made a conscious choice not to write certain thoughts down. If you extrapolate this concept, the decision to change one’s behavior out of a fear of surveillance in other forms, it could create devastating psychological ripple effects. From the book Stasiland, another former GDR citizen, Julia, said,

“You’d go mad, if you thought about it all the time.”

She describes her experiences telephoning her overseas boyfriend,

“When I hung up I’d say goodnight to him, then I’d say, ‘Night all,’ to the others listening in, I meant it as a joke. I didn’t let myself really think about whether there was another person on the line.”

Julia felt that somehow she was actually able to tune out the worry. Calling it ‘paranoia’ would be inaccurate since, statistically speaking, the chances of the Stasi monitoring a telephone call between a foreigner and a GDR citizen was extremely high. I failed to find diagnosed cases of PTSD from people who lived under the Stasi and wondered about the philosophical underpinnings that might explain if it was a reaction to cognitive dissonance that lead to this, or if it was something else entirely.

“The Stasi Persecution Syndrome”, a 1991 research paper, makes the case that people under the Stasi experienced a unique type of PTSD that was more nuanced and harder to diagnose than typical PTSD. The paper concludes that over 50,000 people who lived in the GDR could suffer from “persisting and paranoid anxieties, re-arousable by specific situations…persecution dreams, mood disturbances, [and] lack of confidence”

I decided to speak to a mental health professional who was well versed in the differences between genuine delusional paranoid schizophrenic thoughts and anxiety issues brought on by the prolonged fear of being watched. I spoke with Matt Likens, a licensed psychotherapist in California. Matt regularly deals with patients who have varying degrees of schizophrenia and upon my request familiarized himself with the Stasi.

Our correspondence is as follows:

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Robbie Martin: “If you aren’t doing anything wrong you don’t have anything to hide” ← what does this statement tell you about the psychological state of the person saying it?

Matt Likens: This statement presumes wrongdoing in and of itself. It’s leading, and it’s meant in a way to intimidate, and if perpetuated, “wrongdoing” is manifested in some way, shape, or form, thus fulfilling the projected belief. The paranoid individual trusts nobody, certainly not himself. He is so terrified of literally not existing, annihilated. Having oneself consumed by fear and dissolution, he must project that upon his environment. This character structure exists not only in the individual, but is internalized by the state, and enacted in its systemic sense of omnipotent control over the masses.

RM: Some people under the Stasi who kept diaries would self-censor their thoughts in case the Stasi ever confiscated it. If that’s not ‘paranoia’, how would you describe that?

ML: Denial of one’s sense of self expression and spontaneous gestures both physically and cognitively causes pathology by definition. The formation of all repressive regimes are a result of the pathological incapacity and intolerance for the individual. Sexuality in particular is denied in these societies. Wilhelm Reich wrote that, “..the goal of sexual suppression is that of producing an individual who is adjusted to the authoritarian order and who will submit to it in spite of all misery and degradation.”

RM: There is something inherently narcissistic about imagining that you have been targeted for surveillance and reacting as if its actually happening in the absence of any evidence. These are characteristics of delusional schizophrenics, but in the GDR where the likelihood of being surveilled was very high, what coping mechanisms could someone use to to stop worrying?

ML: One of the most common and well utilized psychic defense mechanisms of an unconsciously paranoid individual is a thing called “reaction formation.” In this mechanism, the individual is capable of defining real and actual feelings towards a threat into its polar opposite, rendering it less threatening to the ego. Individuals under the rule of repressive organizations such as the Stasi understandably utilized reaction formation to minimize paranoia.

RM: Reaction formation sounds like the opposite of willful blindness, what segments of the population do you think fell into these opposing camps?

ML: Poor, sick, and psychologically fragile individuals have a vested interest in willful ignorance, as they live with day to day stress that more privileged individuals need not worry about as much. I think that parents in particular naturally became far more likely to act in accordance to Stasi rule and law to protect the emotional health of their children.

RM: What about people labeling themselves as ‘not important enough’ to be surveilled, what kind of psychological side effects could a thought like that have?

ML: Labeling oneself as “not important enough” to be watched is a powerful way of eliminating real and legitimate concern for one’s safety. This individual feels intense insecurity within himself for various reasons. I also like to think that individuals who minimize their sense of self importance as “the poor me Narcissist.”

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Stasi kept such detailed records that citizens today can go to a special facility and request any records that were compiled on them, and then sit and read their dossier. Undeniably this access provides some catharsis because it attempts to answer the ever burning question in the back of many a GDR citizen’s mind, “was I being watched?”. Many former GDR citizens were surprised to find that the answer was yes, they were indeed being watched, and some of them far more than others.

What about the people who didn’t care to inquire even after being given the privilege? Perhaps many of them had already decided long ago that they were “not important enough.” The lingering after effects of mass surveillance continue to reverberate long after the Stasi’s demise.

written by Robbie Martin with contributions from Laurie Kirchner

follow Robbie on twitter @FluorescentGrey