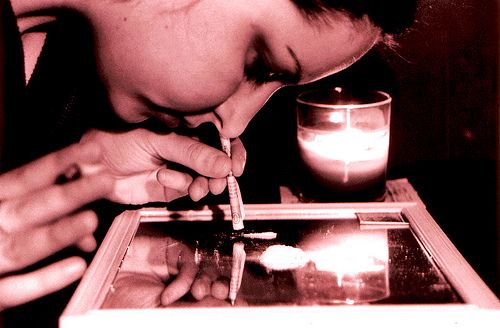

The following is an excerpt from an article called The Mystery of the Tainted Cocaine, Part II: How It’s Made, How It Moves, and Who Might Be Cutting It with a Deadly Cattle-Deworming Drug

THE STRANGER– Diego was 23 years old, a poor Colombian living in a poor section of Cali, when his girlfriend had the baby. He was broke—everybody was broke—but his grandmother knew where he could earn some money: He could go work the coca plantations in the hinterlands like she had. She could get him a job working for FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, Colombia’s Marxist-Leninist guerrilla army), which was better than working for the right-wing paramilitaries.

Diego is not his real name, and he’s currently living in a different Latin American country—otherwise, he said, he wouldn’t be talking to me.

“Not one person I met out there used cocaine,” Diego said. “We would

chew on the leaves—to kill the hunger, the fatigue, to stop the pain of

the work. You’d get bit by spiders and scorpions, mosquitoes or snakes,

and you’d chew so you wouldn’t feel the pain. Some people believed the

coca leaves would stop the poison and save your life.”

“Not one person I met out there used cocaine,” Diego said. “We would

chew on the leaves—to kill the hunger, the fatigue, to stop the pain of

the work. You’d get bit by spiders and scorpions, mosquitoes or snakes,

and you’d chew so you wouldn’t feel the pain. Some people believed the

coca leaves would stop the poison and save your life.”

At his peak earning period, Diego was making the equivalent of US$600 per month. “Back then, that was good cash and it was fast,” he said. It was incredibly dangerous, too: People would go back home with wads of money, usually to bring to their families, and get robbed and killed along the way, sometimes by the same people they’d been working with in the fields for four or five months. When Diego traveled, he always went with an entourage of uncles or cousins.

After a while, Diego graduated from the fields to the “factory,” which was more like a shed, where he helped turn the raw leaves into cocaine paste. “Making the paste is gnarly,” his girlfriend said. “That’s where the real scars come in.”

“There’s a big pool with all the leaves, a big wood tub,” Diego explained. Workers would pour leaves into the tub, stomp them down, and then add gasoline to extract the cocaine alkaloids. “That’s the easiest way for the government to find the camps,” Diego said. “Gasoline is expensive, and most farmers don’t use that much—sugarcane and bananas are all farmed by hand—so you find whoever’s buying vats and vats of gasoline.”

They’d lay a tarp over the tub for 24 hours, with someone stirring the gasoline-coca stew every four or five hours. Then they’d taste the brew to see if it was strong enough. If it numbed the tongue, it was good. If not, it needed more chemicals. Diego doesn’t remember exactly which chemicals they used: “There were a lot of chemicals.” Eventually, they’d pull the plug on the tubs, collect the cocainized gasoline, add ammonia and sulfuric acid, and chemically reduce the brew into a paste that was taken elsewhere to be turned into cocaine hydrochloride—powder.

Diego and the other workers were encouraged to spit into the tubs holding gas and coca, and even pass spit-mugs around the camp, under the premise that saliva helped the extraction process. Workers were also encouraged to ash their cigarettes into the vats, perhaps because traditional coca chewers sometimes added a dab of quicklime or the ash of burned quinoa plants to their wad of coca. (Diego said he wasn’t sure why.)

Then there were the unauthorized additives. “Sometimes we’d piss or shit in the vats, just to be fuckers,” Diego said. “Only the rich use cocaine, and we thought it was funny.”

The territory where Diego was working—he still isn’t 100 percent sure where they were—was a death zone. The paramilitaries and guerrillas were fighting upriver, and he said that sometimes when he went to fetch water, he’d see dead bodies or severed limbs floating past. “I often heard people say things like ‘Yesterday I saw four bodies going down,'” Diego said. “All the time, people were talking about bodies. A lot of times they were tied together, big groups of people.”

Stories circulated from the guerrillas to the workers about small bands of soldiers who “went to make some business away from the group” and were savaged by larger groups of paramilitaries: “First they cut their hands off, then they cut their legs, and then they’d kill them.” The threat of infighting and defection was constant, as workers felt the tempting urge to abscond with packages of paste and sell them on their own.

Then, of course, there was the guerrilla war. In nearby villages, guerrillas and paramilitaries enforced curfews, telling villagers to “go to bed early, because if we see anyone walking around after 10:00 p.m., we’ll kill them.” They also went from village to village, Diego said, conscripting boys for their armies, sometimes leaving notes under people’s doors ordering them to bring their sons to the town center (the church, the plaza) at a certain time. If anyone refused, the soldiers might return to murder the entire family.

***

Diego never worked on the hydrochloride processing, the most chemically advanced and sensitive part of the process—the stage when the paste is turned into powder and, presumably, the stage at which levamisole, a cattle-deworming medicine that’s been showing up in the world’s cocaine supply, is added. As covered in the first part of this series—”The Mystery of the Tainted Cocaine,” August 19—the DEA reported finding levamisole in 73.2 percent of cocaine seized in the United States in 2009, up from a paltry 1.9 percent in 2005. The DEA has also found levamisole-tainted cocaine in busts in Colombia and even in the plastic laminate on glossy calendars shipped into the U.S.—the laminate itself is impregnated with cocaine. (The DEA has agents working across Latin America.) This indicates that levamisole is being added at the source, in the labs where the paste is turned to powder.

When levamisole is ingested by humans, it can trigger a catastrophic immune-system crash called agranulocytosis; it has led to an unknown number of hospitalizations and multiple deaths among cocaine users in the past two years. Physicians in Seattle have reported seeing the same cocaine users land in the hospital with agranulocytosis on multiple occasions.

Levamisole is an unusual—and unprecedented—cutting agent because it’s more expensive than other cuts, it makes some customers sick, and it’s being cut into the cocaine before it hits the United States. Smugglers typically prefer to move pure product, which is less bulky and results in less chance of detection. “The Mystery of the Tainted Cocaine” offered a few theories about why South American drug manufacturers (mostly Colombian) are cutting their cocaine with levamisole.

A quick review of those theories:

1. Levamisole might produce a cocainelike stimulant effect either on its own or in conjunction with cocaine (in 2004, racehorses treated with levamisole were found to metabolize the deworming drug into an amphetamine-like stimulant called aminorex), meaning the product could produce a more substantial high with less pure cocaine.

2. Levamisole, unlike other cutting agents, retains the iridescent, fish-scale sheen of pure cocaine, making it easier to visually pass off levamisole-tainted cocaine as pure.

3. Levamisole passes the “bleach test,” a quick street test that reveals cuts like sugar or lidocaine (but, because of a chemical anomaly, not levamisole).

4. Levamisole is a bulking agent for crack. Making crack involves purifying cocaine and washing out the cutting agents, but levamisole molecules slip through this process—meaning a dealer can produce more volume of crack with less pure cocaine.

***

Read the full article on The Mystery of the Tainted Cocaine, Part II: How It’s Made, How It Moves, and Who Might Be Cutting It with a Deadly Cattle-Deworming Drug

Written by Brendan Kiley

Photo by Flickr user Andronicusmax

© COPYRIGHT THE STRANGER, 2010