The Declaration has uncovered troubling revelations regarding law enforcement operations at Philadelphia’s Delaware Valley Intelligence Center (DVIC), which include the fact that the DVIC, an “all crimes, all hazards” fusion center that assists law enforcement agencies in four states, appears to operate without any privacy policy in place, while its privacy officer position has been vacant since 2010.

In a related development, before the fusion center officially opened, the Philadelphia Police Department operated what one private contractor and a Senate subcommittee labeled a “DVIC Cell”. This unit’s existence indicates probable Constitutional violations dating as far back as 2009, as there doesn’t appear to be any indication of privacy or civil liberties protections attached to the “cell’s” operations.

If the Policy Exists, We Won’t Show it to You

Our research into the South Philly fusion center began in the summer of 2012. At that time the only readily discoverable item of any official nature was a brochure made by architect LR Kimball. Formal inquiries, which began in January of 2013, followed by multiple editorial admonitions published on our website and repeated communication with officials both on and off the record over a 10-month period, have not yielded any official policies. Local police officials have been unwilling – or unable – to produce any documents. They have on numerous occasions tried to assure us that a policy exists.

The Declaration also contacted the Department of Homeland Security’s Civil Liberties office, who upon first contact told the Declaration they would quickly locate the document. Our inquiry is now frozen after being passed to the Fusion Center Training Coordinator Ada Albright, whose final communication with us was a deferral to a telephone number which the Declaration has called countless times.

The officer or employee who answered the phone and confirmed that he was indeed at the DVIC told us that he knew Director Walt Smith already had our request, and that “he’d be best to deal with it.” The stonewall continues.

Additionally, a thorough online search for a DVIC policy will lead you to the National Fusion Center Association website and their list of member facility’s privacy policies. The “Delaware Valley Fusion Center” is on the page, with no link to a policy. A very important note sits at the bottom of that page:

FY 2010 DHS grant funds may not be used to support fusion center-related initiatives unless the fusion center is able to certify that privacy and civil rights/civil liberties (CR/CL) protections are in place that are determined to be at least as comprehensive as the ISE Privacy Guidelines by the ISE Privacy Guidelines Committee (PGC) within 6 months of the award date on this FY 2010 award. If these protections have not been submitted for review and on file with the ISE PGC, DHS grants funds may only be leveraged to support the development and/or completion of the fusion center’s privacy protections requirements.

- A list of privacy policies on the NFCA website shows the DVIC, among a number of other fusion centers, missing a link to a document.

SEPTA police chief Thomas Nestel III, the DVIC’s privacy officer until July of 2010, told The Declaration that he resigned because he could not perform the on-site, full time duties he felt the position required. He believes he had “seen the final draft approved by the Department of Homeland Security.”

Furthermore, in an emailed statement given to us this morning, Nestel says that he “assisted in the creation of the privacy policy and it does exist. Since I no longer hold a position with the DVIC, I am reluctant to release the policy without [Philadelphia Police Inspector Walt Smith’s] permission.”*

Another law enforcement official, on condition of anonymity, also confirms that the DVIC has yet to hire a privacy officer, and describes the facility as not yet fully operational – despite a much-publicized opening on June 28th of this year – in part because the DVIC plans to hire “civilian intelligence analysts.”

These revelations cast strong doubt on the legality of the DVIC’s operations, as fusion centers across the country must adhere to basic standards – outlined in the Department of Homeland Security’s Fusion Center Guidelines as well as the agency’s Baseline Capabilities supplement – standards that include civil liberty and privacy protections. These standards must be implemented in order to receive federal funding.

Privacy guidelines, which the Department of Homeland Security provides a template for on its website and which other fusion centers across the country have in place, establish protocols for the types of intelligence DVIC analysts gather, as well as how that information can be used or disseminated to federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies throughout the four-state region.

Pre-Crime, Suspicious Activity Reporting, and No Privacy: A Troubling Mix

One facet of a fusion center’s day-to-day operations involves either civilian or privatized intelligence analysts examining “suspicious activity reports” filed by law enforcement. These analysts then create threat assessments based on these reports and will often upload them to a federal database, such as the FBI’s e-Guardian system. These assessments are accessible to other local, state, and federal agencies too, as part of a networked law enforcement ecosystem.

During last month’s International Association of Chiefs of Police conference in Philadelphia, The Declaration had the opportunity to attend a presentation on the controversial Nationwide Suspicious Activity Reporting Initiative, often known as “See Something, Say Something.”

David Sobzyk, the scheduled speaker, asserted almost immediately after beginning the presentation that the Nationwide SAR Initiative (NSI) contains built-in privacy and civil liberties protections, yet in the same breath notes that the NSI has 16 behaviors which authorities claim are “indicative of terrorist activity”. In other words, “pre-crime” behavior that could deem an individual or group of people eligible for increased scrutiny by authorities. Other revealing statistics cited by Sobzyk include the fact that 57% of fusion center directors have less than one year of experience; over 85,000 emergency personnel ranging from police officers to 9-1-1 operators and EMS workers have taken SAR training; and a standard SAR training for emergency personnel only consists of a one hour course.

It’s no surprise, then, that a recent ACLU document dump of a Los Angeles fusion center’s suspicious activity reporting made quite a stir among civil libertarians and the press – and this particular center has a published and publicly available privacy policy.

The Declaration submitted a Right-to-Know request in September with the police department for DVIC suspicious activity reporting, which was then rejected. We have since refiled, will appeal if denied again, and are prepared to litigate if necessary.

The potential for operational abuse at the DVIC, then, only increases the need for Constitutional protections that will only come with increased oversight by lawmakers and public scrutiny.

The DVIC’s Troubled Birth

As previously reported, the DVIC received intense criticism from a bi-partisan Senate subcommittee in October of 2012. Their findings indicated (Page 72) that federal grant money was likely being misappropriated by Southeastern Pennsylvania Regional Task Force (SEPA-RTF) officials. SEPA-RTF is multi-county task force that obtained grant funds for a regional intelligence center through the FEMA Homeland Security Grant Program in 2006, and with a consortium of private contractors named the System of Systems Security Consortium (SOSSEC, Inc), was tasked with developing and making the fusion center operational while adhering to federal grant regulations.

According to the subcommittee’s conclusions, the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (PEMA) cut off federal grant money to SEPA-RTF and DVIC development in 2011, because PEMA became aware of plans to illegally use those funds for construction of a Philadelphia Police Department Real Time Crime center at the site of what would become the fusion center. The Senate subcommittee report notes that any planned use of Homeland Security grant money for building construction is prohibited by federal law.

Another curious thread contained in the Senate report, and one which may be another reason PEMA felt it necessary to pull funding in 2011: the existence of a fusion center, listed on the DHS website, that in reality “didn’t exist” according to FEMA testimony before the Senate subcommittee.

The contracting agent tasked with planning and developing the DVIC from 2009 until December of 2011, SOSSEC, Inc., also assisted in the creation of a “DVIC Cell”, a precursor to the current facility.

SOSSEC Vice President Eugene Del Coco, in a lengthy interview with The Declaration this week, revealed the existence of this offsite “microcosm” fusion center launched on July 15th, 2011. Because the DVIC project was experimental, in that it brought together resources and contacts from every jurisdictional tier within a large geographic area, Del Coco says DVIC planners thought it beneficial to establish a prototype operation where a minimal staff could familiarize themselves with the concept of an intelligence center, and gain practical experience and insight into technology and information sharing practices. This offsite center was relocated to the DVIC facility in December, according to a schedule we obtained, and is quite likely one of the mysterious “virtual fusion centers” referred to in testimony by DHS to the same Senate Subcommittee in response to questions about why the DHS listed centers on its site that it knew did not physically exist.

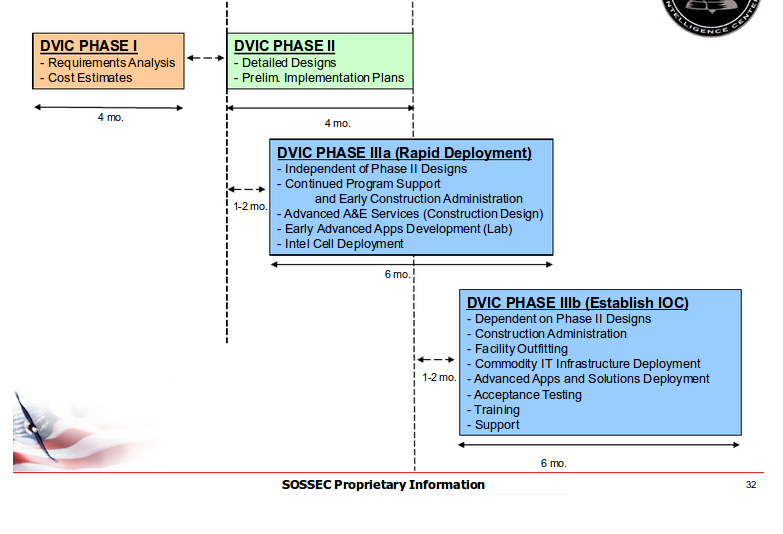

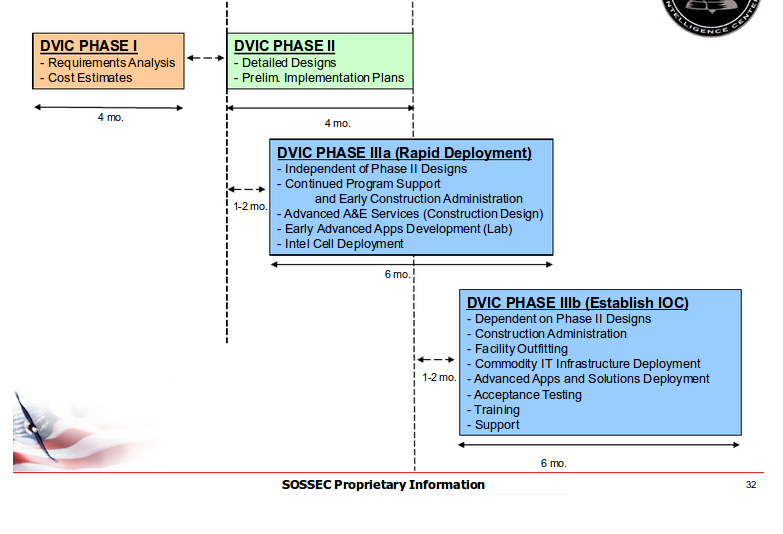

While the general notion of providing advance training to fusion center personnel is rational, given the sensitivity of the operation, the existence of the “Cell” is another example in a litany of cases where the fusion center has been conducting operations which pose serious dangers to Constitutional protections, without significant oversight, and with no record available to the public as to how authorities are ensuring those protections. Del Coco says SOSSEC was originally supposed to complete Phase III-b, “Implementation,” but in December 2011, at the request of the city and SEPA-RTF, relinquished all fusion center responsibilities.

- SOSSEC’s Del Coco said that the original three phase project was split by SEPA-RTF into two sub-phases for its third stage, for which the city Philadelphia assumed control

It is Time for Answers

In October, the DVIC facility was host to a Mounted Unit ceremony, an Asian American Advisory Board meeting which apparently included a briefing on the police department’s intelligence gathering practices for members, and an untold number of formal and informal tours for out of town colleagues during the recent International Association of Chiefs of Police, including a former government intelligence officer who now works for IBM and who requested their name not be used for this article. It only seems fair, by matter not only of best transparency practices but simple intuition, that a privacy policy – the most conspicuous public offering regarding the facility – should indeed be available to the public.

Written by Dustin Slaughter and Kenneth Lipp, Image by Dustin Slaughter