MEDIA ROOTS – Recently we caught up with director Dean Puckett and Dr. Nafeez Mossadeq Ahmed, the creators of the film Crisis of Civilization. Puckett discusses his background as an activist and why he believes corporate media is becoming more irrelevant by the day. Dr. Ahmed sheds light on the true scope of Al Qaeda as well as the Pentagon’s new “lily pad” base system.

Be sure to check out our previous film review for Crisis of Civilization.

***

Interview with filmmaker and director Dean Puckett

Interview with filmmaker and director Dean Puckett

You have had some experience as an activist I understand. You chained yourself to a tree to save a community from being bulldozed, or something along those lines? Please talk about that.

Sure, well firstly, it wasn’t a tree. My hand was chained inside a concrete barrel which was attached to the gates of Dale Farm. Dale Farm was the largest Traveller community of its kind in Britain. It consisted of nearly a hundred plots of land and at its peak, over a thousand residents of Irish Traveller and English Gypsy heritage. I spent 6 weeks living in the community there as part of a resistance to an eviction threat by the local council. Unfortunately we failed and Basildon Borough Council evicted 90 families (about 500 people, many of them children) from the 52 plots of land at Dale Farm because they didn’t have planning permission even though they owned the land that they were living on.

There has been much written about Dale Farm but I think the crux of it is that there is a lot of prejudice against Gypsy and Traveller communities in the UK which gave the Conservative Government the remit to carry out what I believe to be a racist eviction. People like to hide behind the bureaucracies of planning law and conservative ideologies which justify violent evictions of children and families. But in reality we have a hypocritical Legal System which is stacked in favour of the wealthy so it is almost impossible for Travellers to find a piece of land to live on in peace in a way which suits their culture. No one has the right to dominate the natural resources of this planet yet Travellers are hounded to the point where a culture is virtually wiped out because they refuse to conform to what is considered ‘normal society.’ As my good friend Simon said, “no court in the land could make the eviction of Dale Farm just,” and that is how I feel about it.

So I was chained to the gates on the day when there was the first real threat of eviction of the community. You can watch the video of me ‘locked on.’ And truth be told I have some regrets about the experience. I don’t regret locking on or being a part of the resistance at Dale Farm but I really regret talking to the media as I feel it trivialized what I was doing. Putting your body in the way of injustice is something which I feel is important but talking to right wing press will always undermine your actions no matter how well you put your points across.

I wasn’t there on the day of the actual eviction of Dale Farm which was the harshest piece of State Violence that we have seen in this country in my lifetime. If you go back there now the whole area has been dug up and destroyed and there are Travellers living on the side of the road. It was utterly pointless but the establishment has shown once again the lengths it will go to protect its most valuable asset: land.

How did Nafeez influence you the most to make this film?

I am attracted to Nafeez’s work because of the way he communicates his ideas which is to analyze global issues such as peak oil, climate change, the war on terror, the destructive nature of neoliberal capitalism from a systems point of view. So he will analyze the root structural causes of these issues without getting caught up in conspiracy theories, or “them and us” type rhetoric. He keeps a level head and is very pragmatic. His work also feels passionate yet not preachy, with a level of humility about history and the possibility that he could be wrong, which I personally find much easier to engage with than many progressive academics whom are sometimes quite dogmatic about their approach.

But also, as a filmmaker, you have to ask yourself, “how can you add to this?” So reading his book I felt like I could bring these ideas to an audience who would not previously have engaged in the text, which is why I felt it was worth spending a year of my life adapting it into a feature length film alongside artist and animator Lucca Benney.

Also I feel like Nafeez is a unique voice being a Muslim and talking about these issues and it’s not something he gets enough credit for in my opinion. Many of these policies affect Muslim communities globally and domestically and so he deserves to have a place. I’m glad this film seems to be making more people aware of his work.

Other than that I have learnt a hell of a lot from him. It was almost like I did a course in international relations and global politics just making the film. We did seven or eight interview sessions, constantly talking back and forth on the phone and working together to make the film and create the final script. Not to mention the community screenings and film festivals we have attended together since last October.

We’ve learnt from each other, as I think I have taught him to communicate his ideas in a more simple way. Due to having to condense it into a 77 minute film I have had to really strip it down and get to the heart of the issue and also in terms of communication I would say stuff like “how can we say this in a less academic way?” or “how can it be clearer?” I have seen this has translated into the real world in talks and articles which Nafeez has produced since. Ultimately through the experience of making the film, and to this day as we see the film find its audience on television and the internet, we have become friends and he has helped me understand the world better. And that in turn has influenced the way I have approached things like activism and the way I communicate ideas.

There’s an irony of using campy, government funded, public educational film clips in the movie and Crisis of Civilization being the new, 21st century version of a public, educational film, if you will. How much is Crisis of Civilization an antidote to mainstream media propaganda and disinformation?

Key to making this film possible was the discovery of internet archives of open source stock footage. I used footage mainly from the Prelinger Archives and AV Geeks collection, carefully selected from watching hundreds of films. It is a world where you find subtle (and not so subtle) metaphors and parallels to shine fresh light on contemporary issues facing our societies. Some of the films are made by institutions like General Motors and Monsanto and so there is some irony in using them to interpret global crises such as food shortages and energy depletion but also from a creative point of view they look wonderful.

I would sit watching them for hours and hours. I became obsessed with these films and immersed myself in this strange corporate parallel universe. The reason they are so fascinating is because they tell us so much about the world we live in. They represent the ideologies that have gotten us into this mess and the films often bring humor and a surreal edge to Nafeez’s factual and academic work. We also made a conscious decision to make the animations beautiful in their simplicity using iconography such as a business monster eating a forest to guide the audience through the thesis.

I think the mainstream media is becoming more and more irrelevant as the images we see on our TV screens become less in parity with the experiences we are having in the real world. As neoliberal capitalism is failing but the talking heads keep saying the same old crap, people will be looking for different voices and hopefully we can be one of them. There is a faux balance that is created with the news here in Britain. They would never report a more radical perspective on an issue that would really be challenging to the status quo, for example “Lets completely change the way we create money.” Their ‘balance’ is always within a very narrow framework.

Independent media and journalism, along with the internet, is revolutionizing the way we perceive the world and I think that the resurgence in documentary film making along with digital technology is really exciting and is something I am proud to be a part of. I think this is why people are turning to documentary because you can actually take the time to explore and explain something in depth. People are looking to delve beneath the headlines and get into the issues, whether it’s an adaptation of a book or a human story that is not even political, we’re seeing more thirst for real journalism and real filmmakers with a voice to be an antidote to the news and media as people try and make sense of the world around them. The real challenge is how to keep our momentum, break down mainstream distribution channels, and communicate to larger audiences without bowing down to mainstream conventions or sensationalism.

***

Interview with Dr. Nafeez Mossadeq Ahmed

Another great documentary is the BBC production, The Power of Nightmares. It purports that Al-Qaeda literally means “the list” and was a C.I.A. created list of mujahideen fighters, under Bin Laden’s leadership, who fought the Soviets. How real is Al-Qaeda and how much is it a C.I.A. created nightmarish, figment of our imagination?

Al-Qaeda is real, but it did very much originate as an intelligence database of Mujahideen recruits. The later British foreign secretary Robin Cook confirmed in the Guardian that Al-Qaeda referred to a CIA database. These recruits were mobilized primarily in Afghanistan to fight the Soviets. However, it would be a mistake to assume that Al-Qaeda is simply, therefore, an extension of the CIA and a figment of our imagination. The recruits that joined Al-Qaeda were drawn from militant strands of Muslim movements in parts of the Muslim world which already existed. Since then, those strands have often solidified. Al-Qaeda does exist and it does have real agency but it is a loose network rather than a hierarchical centralized structure and it’s precisely this looseness that makes it vulnerable to infiltration, penetration, and manipulation from outside.

Al-Qaeda has also remained fundamentally dependent on a variety of state agencies for support, namely, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Qatar, the UAE, to name a few. As these are to a large extent client regimes of the US and UK, there is scope for manipulation through strategic provision and withdrawal of aid. So, in summary, yes there are real militant Islamist extremists out there, some of them affiliated with a network of Mujahideen fighters associated with a core group originally trained with the logistical and financial support of the CIA. In this context, it would be too simplistic to simply assert that Al-Qaeda is a “figment of our imagination.” On the other hand, there is evidence that the Al-Qaeda label has been misapplied, sometimes deliberately, by Western military intelligence agencies to broadly demonize social groups whose links with Al-Qaeda are in reality tenuous (e.g. Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb: despite some real elements of Al-Qaeda being involved in some cases, many others do not withstand scrutiny – e.g. see the work of Jeremy Keenan). Equally, cases where Al-Qaeda do appear to be involved are underplayed and the al-Qaeda element is overlooked when it suits certain geostrategic interests (e.g. links of the 7/7 bombers with al-Qaeda networks in the Balkans; the role of the west in financing Al-Qaeda Mujahideen networks in Bosnia, Kosovo and Macedonia).

Since 9-11, the United States military has been implementing the “lilly pad” base system; around 50 smaller bases, scattered around the world with small troop numbers, spartan amenities and complete with pre-equipped weaponry. What does this new strategy say about the American empire in the 21st century?

Successive US military planning and national security strategy documents confirm that the US continues to adopt a military posture in which it self-identifies as a unilateral hegemonic power with ultimate responsibility for the integrity of the existing global political and economic order. To this end, the US has attempted to spawn a network of bases in key strategic regions around the world with a view to enable a unique capacity to mobilize military forces at will, with speed, anywhere in the world, and further, to potentially fight wars in multiple theatres. They are a way of continuing to encroach on and contain the power of US rivals like Russia and China.

However, the distinctive quality of the lilly pad system is to focus on less public forms of military penetration into diverse geographical locations, to empower intelligence functions and covert operations capability in a way unlikely to solicit significant public awareness and opposition. It is also linked to a need for greater efficiency in military budgets, facing the strain in the context of continuing global recession.

***

Adam Miezio for Media Roots.

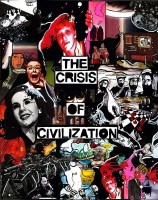

Cover art created by Abby Martin.